AI companies train their models on vast amounts of personal data, and the stakes are high. With its public announcement to train its models on user-generated content from Facebook and Instagram, Meta captured all the attention. Recently, two NGOs took Meta to German courts to stop the social media giant, arguing the training would violate both the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the EU Digital Markets Act (DMA). Both were unsuccessful. Shortcomings of the judgments, and undisclosed details on the procedure in Cologne raise serious concerns that EU law is not effectively enforced under the pressure of the AI hype. Courts and supervisors must demand substantial information on privacy – that AI companies can easily gain by lawfully training and testing their models for research purposes alone.

Disclaimer: For undisclosed information on the procedure in Cologne, the author spoke to two sources that were present at the oral hearing. One is involved in the proceedings on the plaintiff’s side; the other is an independent observer. Both sources provided consistent information on the course of the hearing and statements by the court and Meta’s representatives. The author furthermore received a partially pseudonomised copy of the minutes of the oral hearing.

Table of Contents

- The rise of generative LLMs – and the scattergun approach to superintelligence

- Meta-AI-morphosis: Iridescent AI training plans

- The legal debate around LLMs: The unknown risks of LLMs

- The application with the Higher Court of Cologne in the case of Meta

- Ignoring formal requirements: Informal statements in lieu of an oath

- The undue weight of an unsubstantiated press release and a loosely related decision

- The court’s flawed legal reasoning

- The court’s complete reversal

- Conclusion on the judgment by the Higher Regional Court of Cologne: „Et hätt noch immer jot jejange“

- The decision of the Higher Regional Court of Schleswig-Holstein

- Effective enforcement of regulatory law: Let AI companies do their job

The rise of generative LLMs – and the scattergun approach to superintelligence

In November 2022, OpenAI releases ChatGPT, enabling online users to interact with a generative large language model (LLM). Since then, generative pre-trained transformers (GPTs), have caused an AI hype, and multiple companies have since developed their own models, including, to name just a few, Google (Gemini), Mistral AI, Anthropic (Claude) – and Meta. In February 2023, Meta releases its first Llama (= Large Language Model Meta AI); more follow, most recently Llama 4, released in April 2025.

In an (alleged) winner-takes-all race to create superintelligence, AI companies follow a scattergun approach: They train their models on vast, often uncurated datasets, proclaim the imminent arrival of AI that outperforms an average human in any task, and hope a breakthrough emerges from the chaos. However, AI might just remain a normal, yet highly risky technology.

Table: Timeline of events

| March 2024 | Meta informs the Irish DPA of its AI training plans (according to the DPA and Meta). |

| 16 July 2024 | The Hamburg DPA, the data protection supervisory authority of the German state Hamburg, where Meta has an office, issues a discussion paper stating that LLMs are not personal data (but see 22 May 2025 below). |

| June 2024 | Meta informs users via email that it changes its privacy policy, entering into force on 26 June (see statement of noyb from 6 June 2024). |

| 6 June 2024 | NGO noyb states it filed complaints in 11 EU Member States, requesting to initiate an urgency procedure under Art. 66 GDPR. |

| 10 June 2024 | Meta publishes a statement, according to which it would build AI for Europeans transparently and responsibly. |

| 14 April 2025 | Meta announces to use public user content, such as public posts and comments from Instagram or Facebook, to train its Llama models to improve performance for European users. |

| 23 April 2025 | The EU Commission issues a decision (C(2025) 2091, published on 18 June 2025, see below) on Meta’s „consent or pay“ advertising model under Art. 29(1)(a), 30(1)(a), and 31(1)(h) of the Digital Markets Act (DMA). |

| 12 May 2025 | The North Rhine-Westphalian consumer protection agency (Verbraucherzentrale NRW) files an application for a provisional prohibition of Meta’s planned AI training with the Higher Regional Court of Cologne. |

| 14 May 2025 | NGO noyb announces that it sends Meta a „cease and desist“ letter over AI training, and considers a European Class Action. |

| 21 May 2025 | The Irish DPA publishes a press release in the night before the court hearing in Cologne, according to which Meta can lawfully train its AI models with European user data, if certain measures are implemented. |

| 22 May 2025 | The hearing at the Higher Regional Court of Cologne takes place… and six hours according to the two sources present. The court hears the Hamburg DPA as Meta’s local supervisor. He, on the spot, abandons his former legal opinion according to which LLMs are not personal data (also cf. here), expresses serious concerns about the compliance of Meta’s AI training with the GDPR, and announces to initiate an urgency procedure to stop Meta in Germany (but see 27 May 2025 below). |

| 23 May 2025 | The court delivers its decision, stating that Meta could train its Llama models, and issues a corresponding press release. |

| 27 May 2025 | The court publishes the written judgment. The Hamburg DPA announces that he, considering the judgment of the Cologne court and in favour of a „consistent European stance“, is not going to initiate a provisional injunction against Meta anymore. Meta initiates its AI training with European user data (see only Hamburg DPA), and updates its privacy policy. As the current privacy policy (as of 16 June 2025), the version from 27 May 2025 refer to the use of data from third parties for the training which was not mentioned in Meta’s announcements. |

| 4 June 2025 | The court issues the minutes of the six-hour hearing, 3 pages in total, that do not provide insights into the discussions at court. The minutes state, for example, that the Hamburg DPA gave a statement, without specifying any of its contents. |

| 18 June 2025 | The EU Commission publishes the full decision (C(2024) 2052 final) on Meta’s „consent or pay“ advertising model under the Digital Markets Act (DMA). |

| 27 June 2025 | The Dutch Foundation for Market Information Research (SOMI) files an application for a provisional prohibition of Meta’s ongoing AI training with the Higher Regional Court of Schleswig-Holstein. |

| 5 August 2025 | The Higher Regional Court of Schleswig-Holstein holds the oral hearing. |

| 12 August 2025 | The Higher Regional Court of Schleswig-Holstein, in its judgment, dismisses the application as inadmissible, arguing that the matter lacks the necessary urgency. |

Meta-AI-morphosis: Iridescent AI training plans

In June 2024, Meta’s plan to train its models on user content from its social media platforms Facebook and Instagram comes to the surface: Meta, via email, informs users cryptically about a privacy policy update. For anyone who bothered to click the provided links and navigate Meta’s maze of privacy documents, it becomes apparent that Meta plans to use and share user content for an „AI technology“ without obtaining consent. However, Meta enables users to object to the use of their data, even though that option is hidden so well in Meta’s social media apps‘ privacy settings that content creators and media outlets share step-by-step tutorials to guide users to the objection form. If Meta had a sense of humour, there would be a „Beware of the Leopard“ pop-up.

On June 6, noyb („none of your business“), an NGO founded by lawyer and privacy activist Maximilian Schrems to improve the enforcement of EU data protection law, states it urged data protection authorities in 11 EU countries to initiate proceedings to stop Meta, pointing out especially that Meta’s new privacy policy would foresee the use of any public and non-public data and no effective right to be forgotten. Indeed, Meta enables users to object to the future use of their data for AI training only.

Shortly after, Meta releases a statement explaining and justifying the planned AI training – and limiting its scope. Meta would use public content only and would not „train [its] Llama models“ on content from underaged users. The training would aim to make Meta’s AI „work better for“ European users by training on data that „reflect their cultures, languages and history“. Days later, Meta adds an update to the statement, expressing disappointment over a request by the Irish Data Protection Authority (hereinafter: Irish DPA) to delay the training.

After that, things go quiet regarding Meta’s AI plans, until Meta, in April 2025, announces it would soon begin training its „AI models“ on Meta AI interactions and public user content by adults. Notably, between the privacy policy change and Meta’s April 2025 statement, Meta’s declared plan has significantly changed. While most statements unspecifically refer to AI models, Meta’s statement from June 2024 relates to both, „Llama“ and the „Meta AI assistant“ which is based on Llama. Presumably, all of Meta’s language processing AI systems and features – whether it is the voice assistant in Meta AI glasses, or the voice message transcription feature in Instagram’s messenger or WhatsApp – use Llama. Llama refers to the models, the AI services are systems based on Llama, just as the chatbot ChatGPT is based on a GPT model by OpenAI. The training data comprise not only texts but also photos and videos, as Llama is a multimodal model. As a foundation model, i.e. general-purpose model, Llama is not limited to use cases for specific domains or tasks.

It is noteworthy that Meta’s current privacy policy states that not only user content but also data on AI interactions and third-party information are used to develop and improve Meta’s AI models. Meta does not further specify which data on AI interactions are used for the training and how, but these could comprise non-public data on AI-based image editing, inputs and outputs of voice message transcriptions, search queries and results and even conversations with chatbots. Meta’s privacy policy refers to „messages you or others receive from, share with or send to Meta’s artificial intelligence technology“. This explicitly comprises user data that other users send to Meta’s AI, for example, voice messages that recipients transcribe (without the sender’s knowledge or consent). Also, Meta might train Llama on non-public conversations with its social media platform chatbots, including Meta’s chatbot that reportedly helped a teenager exploring methods to kill himself and custom chatbots by users, for example a disturbing Kurt Cobain chatbot that confabulates about the grunge musician’s suicide.

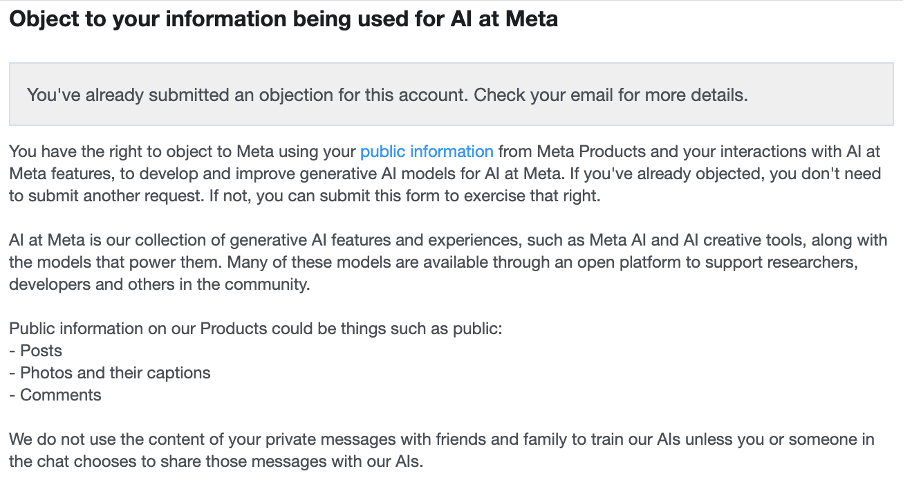

Edit, 20 September 2025: Metas objection form, that can be found in the Meta Privacy Center, even explicitly states that it trains Llama on private messages. According to Meta, users can object to the use of their public information and their interactions with AI. It must therefore be concluded that AI interactions of users who do not object are used to train Llama, whether the AI interactions are public or not. Furthermore, Meta’s information on objection states that Llama is not trained on „the content of private messages with friends and family“ „unless […] someone in the chat chooses to share those messages with our AIs“.

Screenshot 1 from Meta’s information on the right to object (20 September 2025)

For all the justified criticism, it can be argued that with its decision to announce the planned use of social media data for training and the implementation of the right to object, Meta has achieved a level of user agency currently unmatched by its rivals. Users of X (formerly known as Twitter) primarily found out that xAI’s model Grok was trained on their tweets by default through a viral post from a user account that does not exist anymore. LinkedIn reportedly trained AI on user data even before updating its privacy policy. It is plausible that multiple, if not all relevant LLMs have been trained on public data from LinkedIn and X.

The legal debate around LLMs: The unknown risks of LLMs

Meta’s announcement sparked outrage among data protection advocates. LLMs have triggered two major debates on training compliance, on the one hand under copyright law, on the other hand under data protection law. LLM training data include both copyrighted material and personal data within the meaning of the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Researchers extracted significant amounts of training data information from LLMs, e.g. from GPT-2 in 2021 and 2022, in large scales from various models including Llama-65B in 2023, from GPT-4, Llama-3 and Claude in 2025, from Llama-3 in 2025. Extracted data include (nearly) verbatim copies of software code, other copyrighted texts and personal contact information. The extraction of personal training data from the models is also referred to as privacy leakage. As research is still at an early stage, at present, knowledge about the „memorisation“ of training data and the efficacy of preventive measures is limited, and most study results do not generalise across domains, models or model versions.

The other LLM-related phenomenon that requires more research is, misleadingly, referred to as „hallucinations„, i.e. the generation of incorrect information by LLMs. That the models fabricate facts that are not in the training data, is hardly surprising since they compose texts based on statistical correlations for given contexts. However, „hallucinations“ are not well understood yet. This concerns not only hallucination mitigation, but already hallucination detection. Distinguishing „hallucinated“ from „memorised“ data is anything but trivial without full access to the training data that themselves include incorrect information.

If we are worried that a model leaks personal data, we should be even more worried about the risk that it generates incorrect information on those concerned.

In terms of data protection, the interplay between training data reproduction and hallucinations is crucial: If we are worried that a model reproduces personal data from the training data, we must be even more worried about the risk that it generates false information about those whose data are included in the training data, violating the EU General Data Protection Regulation’s (GDPR’s) data accuracy principle.

The application with the Higher Court of Cologne in the case of Meta

Represented by lawfirm Spirit Legal, the North Rhine-Westphalian consumer protection agency (Verbraucherzentrale NRW), after an unsuccessful cease-and-desist letter, in May 2025, files an application for a provisional prohibition of Meta’s AI training with the Higher Regional Court of Cologne, arguing that Meta would lack a legal basis for the training under the GDPR, and building an AI training dataset based on data from both Instagram and Facebook would violate the EU Digital Markets Act (DMA). Arguably, the case would have posed an extraordinary challenge to any court, because it requires judges to delve into EU data protection law, data law, and technological aspects of LLMs within the framework of expedited proceedings which afford little time for a review. Additionally, national courts and authorities are under latent pressure to avoid unilateral national action regarding the lawfulness of AI training, though especially judges must be capable of withstanding such pressure. On 23 May 2025, the 15th Civil Senate of the Higher Regional Court of Cologne – without the involvement of its usually presiding judge Richter – decides to reject the emergency application. The same day that the court publishes its written judgment, on 27 May 2025, Meta starts to train Llama on social media content. Both details of the procedure and the court’s legal reasoning raise concerns about the enforcement of EU regulatory law in the realm of AI.

In the Cologne proceedings, four aspects stand out:

- The court ignored formal requirements.

- The court gave undue weight to two documents.

- The legal reasoning of the court is fundamentally flawed.

- The decision marks a complete reversal of the opinions the court gave during the oral hearing.

Ignoring formal requirements: Informal statements in lieu of an oath

One unsettling aspect of the Cologne procedure is the „evidence“ that the decision is based on. Within the framework of expedited proceedings that aim at quick decisions in urgent cases, judges carry out cursory reviews only, and largely rely on „affirmations in lieu of an oath“ (in German: eidesstattliche Versicherungen). The term refers to formal statements by the parties for which the German Criminal Code ensures efficacy by criminalising false statements. The Cologne court bases its decision on alleged „affirmations in lieu of an oath“ by Meta’s Director for GenAI Product Management Joonas Hjelt whose name is pseudonymised in the published version of the judgment but who is easily identifiable based on his position and LinkedIn.

As the two sources report from the oral hearing, Hjelt’s statements were informal (one with an informal electronic signature, one as a copy in the hearing), i.e. they do not meet the formal requirements under German law, and the plaintiff’s side explicitly pointed that out. It is unclear why the judgment insofar refers to „affirmations in lieu of an oath“, as the court could have legitimately considered the informal statements. The judges would simply have had to further substantiated the given statements. What also called for increased scrutiny is the specific constellation. It is not a natural given that the possibility of prosecution in Germany would bother Hjelt who resides in California (as also pointed out by Wasilewski in CR). For all the allure of Berghain, Oktoberfest and Cologne’s signature beer Kölsch, Germany might never make it to Hjelt’s travel list. The author has no intention to accuse Hjelt of giving false statements, and no evidence implies that he did so. But it is difficult to understand why a court would rely on such a statement coming from a company that is involved in the speculative and ill-defined, yet aggressive race for superintelligence. As a side note, there is profound irony in attempting to build a higher form of intelligence from the digital garbage dump of user-generated content, albeit Meta has some data that might indeed be valuable for AI development, e.g. images with captions and network data.

The Cologne court, reasonably, should have dispelled foreseeable doubts about the judgment by not relying too much on Hjelt’s statements, or by obtaining formal affirmations in lieu of an oath and substantiating their efficacy in the concrete case. Additionally, Hjelt’s statements seem to have a very limited scope and might lack any substantiation. For example, Hjelt’s statement on the compliance of the objection form, as summarised in the judgment, relates to the present only even though a flawed objection feature might have rendered objections of Facebook and Instagram users ineffective. This corresponds to the Irish DPA’s press release according to which Meta had to make amendments to a formerly insufficient objection feature.

The undue weight of an unsubstantiated press release and a loosely related decision

How much significance should a court attach to a one-page document without any legal reasoning by the Irish DPA from the night before?

A closer look at the press release and its apparent influence on the judgment is disturbing. It was issued the night before the oral hearing by Meta’s lead data protection supervisor in the EU, the Irish DPA – that is so notoriously processor-friendly that it attracts data controllers to locate in Ireland (e.g. Apple and Intel to name two more big techs). According to the press release, Meta has implemented „significant measures and improvements“ that the Irish DPA had „recommended“ after obtaining other DPAs‘ „feedback“. As the two sources report from the oral hearing, the court explicitly stated that it would likely have to concur with the DPA’s assessment. This arguably conflicts with the separation of powers (Wasilewski in CR). What is fishier, however, is the timing of the press release. Shamed be she who thinks evil of it… Would an EU DPA coordinate with Meta to influence a court? And, more importantly, even if the consistent application of the GDPR is desirable, should a court feel bound to a one-page document from the night before that does not refer to a single GDPR provision when addressing a legal problem as complex as the question of whether AI training complies with the GDPR? The press release indicates a mere consultation, but not a violation procedure. The court was even aware of this: It states that Meta’s competent local supervisory authority in the German state of Hamburg, the Hamburg DPA, outlined the Irish DPA’s legal opinion on Meta’s AI training in the oral hearing. As stated in the judgment, the Irish DPA has not prohibited the AI training yet (! – „bislang“, para. 104 of the judgment) to closely monitor the consequences first.

As the two sources report from the court room, the Irish DPA plans to initiate proceedings on potential GDPR violations against Meta not before October. And Meta might face a huge fine. Albeit the supervisory authority falls at the processor-friendly side of the spectrum and is delaying its decision on GDPR violations through Meta’s AI training, it has imposed large fines before, e.g. a 530 million Euro fine on TikTok for data transfers to China, and, following a binding decision by the European Data Protection Board (EDPB), a 1.2 billion Euro fine on facebook for data transfers to the US. EU supervisory authorities might already be aware of violations – and be monitoring the consequences to determine appropriate sanctions and calculate a fine for Meta. The Hamburg DPA, according to the two sources present at the oral hearing, changed his initial legal opinion on the applicability of the GDPR to LLMs over the specific case, and announced in the court room to adopt provisional measures against Meta on the national level immediately, before he dropped that plan over the judgment.

Another worrying detail of the proceedings concerns the alleged violation of the Digital Markets Act (DMA). The DMA aims to ensure fair and contestable markets in the digital sector. The provision at dispute, Art. 5(2) subpara 1 (b) DMA prohibits providers of core platform services such as social media platforms from combining personal data from different core platform services (KĂĽnstner, “AI Training under the Radar of the DMA?”, CR 2025, p. 493 at paras. 4 and 10). To ensure the harmonised application of the DMA, national courts shall not issue decisions that run counter to or conflict with decisions by the EU Commission. In the hearing, this aspect took three hours to discuss, as the two sources told the author: Meta’s representatives claimed Meta had received a Commission decision that would contradict the finding that Meta’s AI training plans violated the DMA. However, Meta’s representants refused to provide the court with the – at that time unpublished – decision, referring to business secrets (cf. para 25 of the judgment). According to the two sources, the court suggested to delay the training for two or three months, or to train Meta’s model on data from only one of Meta’s social media platforms first, which Meta disagreed to, stating the latter was impossible. When the court insisted on receiving the decision, Meta emailed an excerpt of less than 2 pages. After seeing the excerpt, the judges stated on the spot they would not follow Meta’s line of argumentation and Meta’s AI training plan would clearly violate the prohibition of combining personal data from different core platform services, such as social media platforms.

Ultimately, however, the court made the opposite decision, arguing the provision would only apply to the targeted combination of data of the same users. Meta would not create user profiles but merely a „data silo“, adding that its interpretation would correspond with the Commission decision excerpt that Meta provided, pointing to one paragraph that, read out of context, supports the court’s narrow interpretation. The judgment apparently prompted (pun intended) the Commission to publish the decision. The decision does not elaborate on the scope of the DMA provision, and the court could have anticipated that even without any access to the decision text or parts of it: The decision concerns Meta’s „Consent or Pay“ model for targeted advertising based on user profiles, and, thus, a case that falls under the DMA provision without any doubt. There was no logical reason for the court to assume that the Commission would give substantial guidance on the scope of a DMA provision in this context.

The court’s flawed legal reasoning

The court’s further legal reasoning is fundamentally flawed. This concerns both, the alleged DMA violation and the question of whether Meta’s training violates the GDPR.

The court’s flimsy arguments on the DMA’s prohibition of data combinations

The court insufficiently considers the DMA’s market regulation purpose, albeit no one, not even Meta, knows whether Meta’s AI training will have much impact.

The court’s reasoning on the interpretation of the DMA provision at dispute leaves the realm of logic (see also KĂĽnstner, “AI Training under the Radar of the DMA?”, CR 2025, p. 493 at paras. 18 – 20). When addressing the purpose and intent of the DMA’s prohibition of combining data, the court points out that not everything that touches upon the purpose and intent of a norm necessarily falls under its scope. This cannot be emphasised enough when the interpretation of a norm is extended beyond its wording, but has zero relevance for what the court tries to argue for: A scope narrower than wording. The court, furthermore, argues that the option to combine data based on user consent Art. 5(2) subpara 2 DMA would only make sense for combinations of data of individual users. However, the consent option is limited to cases where users have the specific choice to opt for a less personalised alternative. And the court insufficiently considers the market regulation purpose of the DMA, especially when it resorts to the rarely logical „knock-out“ argument that inevitably comes up in every AI-related legal debate: The legislator would not have had AI training „in mind“. What the legislator had in mind is clear: Gatekeepers shall be prevented from exploiting competitive advantages in accumulating personal data and, as a result, increase barriers to enter for potential competitors. This crucially argues against an understanding of the provision that is limited to specific technologies or processing purposes, and for an understanding that extends to the use of combined user data to train large language models. At present, however, likely no one, not even Meta, knows whether training Llama on social media data will substantially improve model performance and impact the market.

Lawfulness of Meta’s AI training under the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)

The most discussed legal question of the case, however, regards the question of whether there is a legal basis for Meta’s AI training under the GDPR. The judgment follows Meta’s legal view and considers legitimate interest (Art. 6(1)(f) GDPR) a sufficient legal basis for Meta’s AI training. Meta has an economic interest in trying to improve Llama with the data it has. However, legitimate interest only provides a legal basis if the data subjects‘ (here: Facebook and Instagram users‘) interests or fundamental rights and freedoms do not override the processor’s (here: Meta’s) interests.

The court’s risk „assessment“: What could possibly go wrong?

When assessing the risks of Meta’s training, the court fails to deliver any substantial arguments for its claim. The balancing of interests requires analysing the relevant facts of the case, considering especially the risks that the processing poses to the concerned data subjects. Even in a cursory review, the risk assessment requires a sufficient understanding of the technology, use cases, systems, user groups, and specific privacy risks. And these risks remain too under-researched for privacy experts to share the court’s confidence on Meta’s AI training.

A court that takes the rule of law seriously cannot let Meta train Llama on personal data, while AI experts do not know much yet.

Rather than performing a substantial cursory legal review, the court works with assumptions and claims. In the facts of the case, given in the judgment, any information on the intended use of the trained – foundation – AI models is missing. The court seems not to be aware of the fact that Meta wants to train a foundation model (Llama), and what it is used for, but this is crucial to assess risks for users. The judgment does neither mention Llama nor any specific social media feature based on it. While a social media platform feature such as transcription or search might not allow for the extraction of personal training data, it is very likely that such data is extracted from Llama (accidentally, or in a targeted manner, especially in privacy research). What is also noteworthy is the fact that the judgment refers to the planned use of data on user interactions with the „AI model“ but assumes these data are public (cf. para 7 of the judgment) – a limitation that Meta’s privacy policy does not indicate. A court that takes the rule of law seriously cannot let Meta train Llama on personal data and unleash it upon humanity, following a „let’s wait and see“ approach.

The data subjects that cannot object, and children’s right to be forgotten by the court

Furthermore, the court has not sufficiently considered all data subjects concerned and the level of protection. The user-generated content that Meta trains Llama on, is not only personal data of users who shared it but also refers to other users and even to natural persons who do not use the platform at all. Meta, however, has no process in place to enable users and non-users to object to the use of their personal data that has been shared through other than their own accounts. To the use of personal data shared by institutional accounts, no one can object to the processing.

Furthermore, many users are minors. While Meta’s policies foresee that children can hold Facebook and Instagram accounts under specific restrictions, Meta does not effectively prevent minors from creating adult accounts based on false age information. Meta, at least for those accounts, has no effective measures in place to protect underaged account holders.

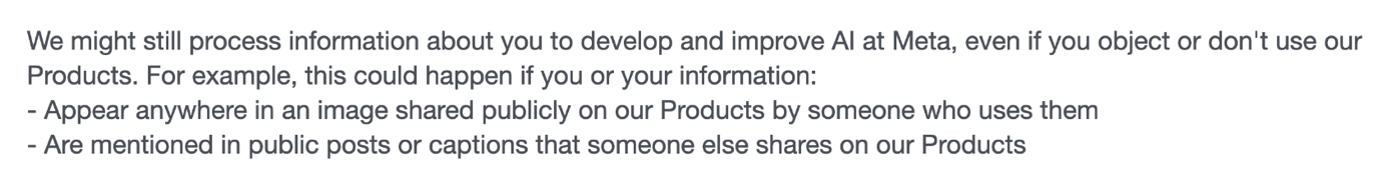

Edit, 20 September 2025: It should be noted that the scope of objections is very limited and does not extend to all personal data of the respective user. In the information on users‘ right to object in the Meta Privacy Center, the company explicitly states that Llama could still be trained on personal data of users who have exercised their right to object. Concretely, this concerns personal data publicly shared by users, or in public posts or caption that other users share on Meta’s „Products“. Meta uses the term „Product“, among others, for Facebook, Messenger, Instagram, including other apps such as Threads.

Screenshot 2 from Meta’s information on the right to object (20 September 2025)

The not so special treatment of special categories of data

The most irritating part of the judgment, however, concerns special categories of data. The court bases their processing on legitimate interest. The GDPR, however, does not foresee a processing of special categories data based on legitimate interest. The court claims that the purpose and intent of the GDPR’s rules on special categories of data would not require the application of the higher requirements for the processing of special categories of data (Art. 9(1) GDPR). This line of argumentation seems wild in the context of a foundation model. In the context of data-driven processing procedures, especially machine learning, special categories of data and proxies for such data are dangerous, as they easily lead to unforeseen model biases, as the example of COMPAS shows. And if the court was aware of the endless possibilities to use Llama, e.g. for decision-making (e.g. administrative decisions or hiring decisions), the judgment would be less confident about its claims.

The court’s complete reversal

Has immense pressure not to interfere with a hyped AI technology and the EU’s plans to build a competitive EU AI market changed the court’s mind?

According to two sources present at the oral hearing in Cologne, the court’s decision was utterly unexpected. To be fair, the court was not bound to legal opinions given in the hearing. Especially for complex matters, post-hearing legal epiphanies are neither surprising nor suspicious per se. Considering the procedural flaws, however, the court’s u-turn gives rise to speculation. Were the judges overwhelmed by the complex matter? Or was the decision informed by explicit or implicit pressure not to interfere with the most hyped AI technology and the EU’s – more or less realistic – aspirations to build a competitive EU AI market?

Conclusion on the judgment by the Higher Regional Court of Cologne: „Et hätt noch immer jot jejange“

Overall, Cologne judgment is an example of judicial failure in the face of big tech’s tactics. The procedural details are disenchanting: The judges, after the oral hearing, changed their minds overnight. The decision is based on hollow assumptions and informal statements by Meta. It was influenced by a one-page press release without any probative value for the case – by the Irish DPA that, as the court itself states, delays initiating violation proceedings against Meta. Rather than with fundamental rights, the Cologne court’s legal reasoning seems to be in line with the Cologne Basic Law (Kölner Grundgesetz), a collection of truisms that serves as a constitution for everyday life and reflects a relaxed, tolerant, pragmatic, and life-affirming philosophy. Its § 3 stipulates „Et hätt noch immer jot jejange“, which roughly translates to: It always went well in the end. Albeit this is a recommendable approach for countless situations in life, it cannot inform a judgment that must satisfy the rule of law. The Cologne judgment threatens to undermine the credibility of the justice system. The court has the chance to make a better decision, when it, based on an in-depth assessment and under higher requirements for evidence, decides on the merits of the case. This decision, however, might come too late for social media users and the EU digital market.

The decision of the Higher Regional Court of Schleswig-Holstein

That is why, after the Cologne ruling, the Dutch Foundation for Market Information Research (SOMI), also represented by Spirit Legal, on 27 June 2025, files an application for a provisional prohibition of Meta’s ongoing AI training with the Higher Regional Court of Schleswig-Holstein. While the Higher Regional Court of Cologne decided about the planned AI training as a future act, based on the risk of a first-time offense, the Higher Regional Court of Schleswig-Holstein deals with the ongoing training, i.e. an (alleged) ongoing infringement, based on the risk of repetition (or continuation).

The court in Schleswig rejected the application as inadmissible, arguing the matter would lack the necessary urgency. It points out that SOMI has been aware of Meta’s AI training plans since Meta’s announcement from 14 April 2025, and concludes that SOMI has waited too long to apply for provisional measures. It is unusual at best that a court dismisses an application for a preliminary injunction regarding an ongoing violation, arguing the plaintiff could have applied for a preliminary injunction regarding a future violation. Both actions, per se, concern different subjects of dispute.

Even under the assumption that both legal actions could concern the same subject of dispute, this is not convincing in Meta’s case due to constantly changing information on the training. Meta’s announced AI training plans were far from being specific in April 2025. According to the two sources that were present at the oral hearing in Cologne, the scope of Meta’s training plans, especially the fact that Meta trains its foundation model Llama on the data, was discussed and clarified only during the hearing, and not included in the Cologne judgment. As SOMI furthermore pointed out, Meta’s current privacy policy (as of 16 June 2025) and the version from 27 May 2025 refer to the use of data from third parties for the training of AI technologies. According to para 58 of the judgment from Schleswig, Meta, contrary to its privacy policy, stated it would not use „technical AI protocol data“ and data provided by partners to train Llama, as these data were useless as training data. The court claims that Meta’s privacy policy would just list potentially („möglicherweise“) processed data categories and would not indicate that the data are used for AI development. The privacy policy indeed states, what data are used depends on the individual circumstances of the user. However, Meta’s privacy policy explicitly says that interactions with Meta’s AI and information from partners are used for the purpose of „develop[ing] and improv[ing] artificial intelligence technology (also called AI at Meta) on Meta Products and for third parties“. Also, inputs and outputs are exempted from Meta’s statement on AI interactions, as summarised in the judgment. Such data comprise, for example, a voice message sent in Instagram and its auto-transcription, or search queries, their results and further user interactions that indicate the success of the search. They are both non-public and, overall, more sensitive than publicly shared content. Should users prepare for Llama leaking their private messages?

Effective enforcement of regulatory law: Let AI companies do their job

The German court procedures concerning Meta’s AI training and its privacy implications raise serious concerns that EU law is not effectively enforced under the pressure of the AI hype. While a harmonised application of EU law is desirable, the high potential impacts of AI on fundamental rights render a „wait and see“ attitude towards AI big techs indefensible. Regulation can serve as a strong economic incentive to strengthen rights, if EU courts and regulators hold AI companies accountable, demand transparent risk assessments, and protect EU citizens from serving as test rabbits. Providing sufficient information on LLMs requires researching privacy risks and their mitigation through training design and privacy measures. For foundation models, studies need to address diverse application scenarios. Lawfully training and testing LLMs solely(!) for research purposes is straightforwardly possible under the GDPR based on legitimate interest and research priviledges laid down in the GDPR and national law of the EU Member States (e.g. Section 55 of the Irish Data Protection Act), cf. Pesch/Magnussen 2025.

Edit note: A former version of this article incorrectly stated, the court received the informal statements by Hjelt via email. However, Meta emailed the Commission decision excerpt only.

Edit note: The author added two passages with screenshots on Meta’s information on the right to object (see „Edit, 20 September 2025“).